Thoughts on the decline of thought in the face of social networks and then I remember...

...I have a book releasing this year

Winter tends to hit in the Midwest like a slide of heavy snow off the limbs of a laden evergreen, thick and dense and interrupting any forward motion you might have built up, obliterating any good intentions of writing email newsletters.

At least, that’s what I’m telling myself.

But! I have updates and events and things to share, so I’ve shoveled myself out of my winter sloth and am providing the requisite missive from the depths of February.

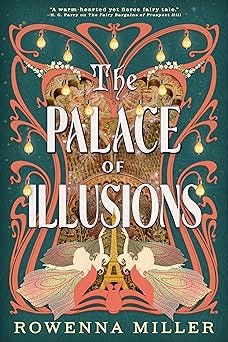

First! The Palace of Illusions is available for pre-order, and I will be dropping a pre-order incentive in March (just as soon as everything arrives from the printer). So—if you pre-order through any of the major outlets or your favorite indie, just save your receipts/proof of purchase/convincing story of your pre-order endeavor, and you can get a fab swag set in the mail (including a signed bookplate—so if you can’t make it to a signing, you can still have a signed book!)

Looking ahead—there are a couple book events planned when Palace launches in June, likely in Indianapolis and South Bend. Watch this space!

Speaking of events, I’ll be at the St. Joseph County library’s main branch for their BookCon on March 29, 11-3. Looking forward to meeting readers and other authors from the region!

For what it’s worth, I think these kinds of events are important. In general, conversations about art, and books, and ideas are important, and doing it in real time with real people so we can actually dig in a little bit, unearth something other than surface vagaries, is important, too. I’ve been having my First Year Writing students read the 2019 Atlantic article “The Dark Psychology of Social Networks” by Jonathan Haidt and Tobias Rose-Stockwell, and I’m struck by how some of the frustrations I feel are reflected in this article. (For what it’s worth—contrary to popular opinion, many of my Gen Z students are highly distrustful of social media and recognize its potential for misuse and abuse, though many of them aren’t really sure how to get away from using it. I sympathize with them.)

One of the elements that Haidt and Rose-Stockwell bring up is the paradoxical loss of wisdom that has accompanied our internet age. Paradoxical, because in our exceptionally connected world, well-furnished with literally everything that’s ever been published, we have greater access to the wisdom of the ages than any generation previous to us. It’s not that people today are naturally stupider or lacking the intellectual capacity to develop wisdom, they argue; it’s that the fire hose of ideas we’re pummeled with online is largely a soup of surface-level reaction and rage-bait. We trace few ideas back to their logical foundations; we interrogate even fewer. We attempt to synthesize disparate concepts rarely. We breathe a sigh of relief to find the algorithm carefully curated to let us consume content that does not challenge us.

Another thing I’ve noticed, over the (ahem) historical period since the founding of the internet—social media used to focus on the individual user producing “content” of some kind (at first, just text posts, later photos and videos, too) and connecting with people *they actually knew.* This developed into forming connections with those they might NOT know outside of the internet, but the model still hinged on your own contribution. You posted, people commented. Others posted, you commented. You knew each other, at least kinda. Now, when I ask how many of my students use social media, most own up to having a few accounts. However, few actually POST anything on those accounts. They just consume, mostly from influencer accounts of people they don’t know from Adam. When the social networks have become vending machines we constantly pull content out of, paying only with our time, the paradigm shifts—there is less engagement, less thoughtfulness, I think, if you aren’t putting anything in yourself.

Maybe I’m being bleak or overstating reality. But my students notice it, too. They cite the “chronically online” for the worst of this behavior. Interestingly, I’ve seen a recovery from the immediate post-COVID semesters in terms of students engaging with each other. When we first came back to in-person classes, my students seemed content to stare at their phones, not talk to each other. I’ve noticed a shift in this behavior—not in all classes, but in many, students cluster together and talk before class. They trade cell numbers so they can form study groups. They talk more in class and cheerfully debate each other, mostly on more benign topics, like whether the Barbie movie was genius or overrated, than more serious or philosophical fare, but it’s a start.

I’ll be the last to say there are no benefits to online spaces. There are—it’s where I connect with most of my writer friends, how I keep in touch with people spread across the globe, how I share photos with far-flung family. But I think my students are onto something when it comes to reaching outside these spaces to form connections, too. They’re correct that we need to combat turning the internet into our sole world, that a lot of our problems might be solved if we were to just “touch grass” once in a while. And in-person connection is, they’re noticing, and I agree, kinda important. It’s less passive. You can’t solely consume. It forces thoughtfulness and engagement and, maybe, in the increased tension of dissonant ideas and contrary opinions, fosters the development of a little wisdom, too.

So that’s why I’ll be at the library next month, and hosting a book launch event or two, and I hope you can make it. Let’s talk!